The Historic Curt Flood Baseball Card...That's Totally Wrong

It's a painful gateway to the modern game

1970 Topps Curt Flood (#360) - Card of the Day

There’s a lot of different ways you could go about celebrating Labor Day with baseball cards.

Yesterday, for example, I ran through five players who clocked in pretty much every day for decades even though they didn’t get a ton of recognition most of the time, and certainly not today. You can read that piece right here if you like.

Today, here in the actual meat of the holiday, I thought we’d highlight a baseball card that stands for the current state of “labor” in the game like maybe none other.

On the surface, the 1970 Topps Curt Flood card is pretty unassuming. Boring, even.

But keen-eyed collectors with a bit of ancient baseball history in their memory banks will recognize right away that the Flood-Phillies marriage doesn’t look quite right. And therein lies the rub in this whole matter.

Flood started his big league career with my Cincinnati Reds back in 1956 at the age of 18. He played in just eight games for Cincy through 1957, but he showed enough all-around ability in the minors to grab attention throughout the game.

The St. Louis Cardinals came calling in the offseason, trading Marty Kutyna, Willard Schmidt, and Ted Wieand to the “Redlegs” in exchange for Flood and fellow outfielder Joe Taylor.

Flood took over the bulk of centerfield duties for the Cardinals right away and hit .261 with ten home runs and 41 RBI as a rookie in 1958. His defense in center was top-notch from the jump, but it took awhile for his bat to gel.

By the time Flood was 25, though, he was a .300 hitter with double-digit home run power, and he won the first of seven straight Gold Gloves. As the Cardinals grew into a perennial pennant contender, Flood’s star rose right along with them.

But after losing an epic seven-game World Series to the Detroit Tigers in 1968, the Cards found divisional play to be treacherous waters. They finished in fourth place in the newly-formed National League East, 13-games behind the eventual world-champion New York Mets.

Exasperating that tough season was an ongoing bout of hard feelings between Flood and Cardinals’ president Gussie Busch. Flood had asked for $90,000 in the new season, while Busch offered just $77,500, a $5000 raise over 1968. By many accounts, Flood felt like Busch was holding a grudge over what he judged to be a costly misplay by Flood on a drive by Jim Northrup in Game 7 of that Fall Classic loss to the Tigers.

Eventually, Flood got his money, but his performance in 1969 was a touch off his normal excellence — he hit .285 with four home runs, 57 RBI, and nine stolen bases. Those numbers were all down from 1968, despite offense rebounding across the game during the summer after “The Year of the Pitcher.”

To ratchet up the tension even more, the players’ union had staged a Spring Training boycott to try and get the owners to beef up their contributions to the pension plan.

So with the Cards coming off a down year, Flood’s numbers slipping at age 31, and ongoing labor strife, Busch decided some changes were in order heading into the 1970s.

On October 7, 1969, the Cardinals traded Flood, Byron Browne, Joe Hoerner, and Tim McCarver to the Phillies in exchange for Dick Allen, Jerry Johnson, and Cookie Rojas. Curt Flood refused to report to his new team.

Flood wanted no part of the Phillies, whom he considered to be a rundown team in a rundown stadium, or Philadelphia fans, whom he considered to be rude and racist. He also didn’t want to uproot his life in St. Louis.

So Flood refused to report to his new team, setting off a firestorm that eventually changed the sport forever.

First, Philadelphia general manager John Quinn met with Flood, and the two of them hashed out a loose agreement that would get the centerfielder in a Phillies uniform at a higher rate of pay.

But Flood also met with union chief Marvin Miller, who told him the MLBPA was willing to help him fight the trade — and baseball’s reserve clause — in court.

The meeting with Miller held sway.

On Christmas Eve, Flood sent a letter to commissioner Bowie Kuhn, declaring himself a free agent who would listen to offers from any team.

Kuhn predictably rejected Flood’s assertion, and Flood in turn followed up with a lawsuit against MLB, alleging that the reserve clause — wherein a team maintained exclusive rights to a player basically forever — violated antitrust laws.

While the case worked its way through the courts, Flood was essentially exiled from the game. Fans across the sport attacked (at least verbally) and/or threatened him at every turn, and many within the game told him he was done.

Who would touch him as a player after he challenged the vaunted structure of the grand old game, after all?

Flood first sat out the 1970 season, still refusing to report to the Phils. That November, Philly traded him to the Washington Senators along with a player to be named later (Jeff Terpko) for Greg Goossen, Gene Martin, and Jeff Terpko.

In the meantime, the Cardinals sent Willie Montañez and Jim Browning to Philadelphia during the 1970 season to make up for the loss of Flood.

Also in the meantime, Topps went ahead and issued the card you see above, showing Flood as a member of the Phillies even though his protest and nascent court battle were well-known in the sport.

At least they went with the old “hide-the-logo” trick instead of airbrushing the Phillies logo across Flood’s forehead.

Flood started 1971 with the Senators but found the going tough everywhere he went. On the diamond, he hit just .200 through 13 April games. Manager Ted Williams stood by his outfielder — publicly, at least — but Flood had had enough and hung up his spikes before May began.

Less than a year later, in March of 1972, Flood’s case made it to the Supreme Court. Major League Baseball won a split decision (5-3), and the players were still stuck with the reserve clause.

But only temporarily.

Buoyed by the divided Supreme Court and confident they were on the right side of the law and basic morality, the players pushed on even as Flood receded into the background — cut out of the MLB fold, whether anyone would officially admit it or not.

In December of 1975, Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith won their own suit against Major League Baseball. The reserve clause was dead and modern free agency was born.

Without Flood and his fight, and his sacrifice, the huge salaries the game supports today would have never been possible. Maybe someone else would have stood his ground and put his career on the line.

Probably, someone would have.

But Flood actually did. And his 1970 Topps card showing him with the Phillies, a card that maybe should have never been made, is about as historic a hunk of cardboard as you’re likely to find in the price range of a common.

Dick in the Thick of It

Dick Allen’s departure from Philadelphia in the Flood trade highlighted the problems Flood himself wanted to avoid. The racism Allen faced in the minors, in Philly, and even in his own clubhouse was no secret, and Allen finally decided he wanted out.

When he demanded a trade in 1970, and the Phillies obliged, sending him to the Cardinals. Flood was no doubt the centerpiece of the package coming the Phils’ way, but of course that didn’t quite pan out for them.

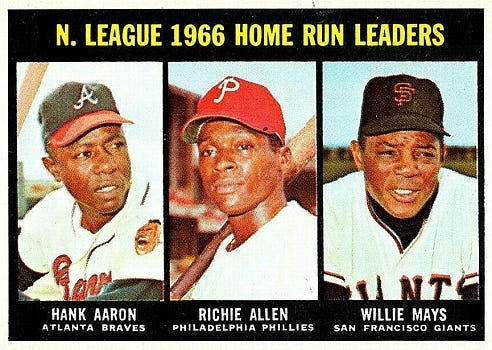

Allen laid down plenty of big numbers and sweet on-field memories during his (first) seven years in Philadelphia, though. Indeed, he was among the greatest and most feared hitters in the National League, as evidenced by the Allen sandwich above, with bun featuring Hank Aaron and Willie Mays.

Read more about Allen and this 1967 Topps dandy right here.

—

That’s all for this not-really-Monday Monday edition.

Happy Labor Day, and thanks for reading.

—Adam

My Baseball Books on Books2Read:

Like these stories and want to support them? Now you can contribute any amount you like via PayPal:

… or Buy Me a Coffee: